Venture Capital Fees Explained: What GPs & LPs Need to Know

When it comes to venture capital (VC), the fee structure of a fund is never the primary reason a Limited Partner (LP) decides to invest. However, it can easily become the deciding factor for not investing. This is why it's crucial for both General Partners (GPs) and LPs to have a clear understanding of the various types of fees in VC. They need to understand what they are charging and being charged and what is considered market standard.

In this blog post, we'll break down the main fees in venture capital and offer some insights from our role as a fund of funds.

Management Fees

Management fees are annual fees paid by a fund’s limited partners to the general partner entity as part of their commitment. These fees cover the operational costs of managing the fund, including salaries, office expenses, software and hardware costs, as well as travel expenses. Typically, management fees range from 1.0% to 2.5% p.a. of the fund’s committed capital. Although it is possible to charge a management fee as a percentage of the fund’s net asset value (NAV), this rarely happens in VC and is not favoured by LPs.

Management fees are generally charged throughout the life of the fund, although they may also be front-loaded, i.e. the fund charges higher annual fees during the investment period and lower annual fees during the remainder of the fund’s duration.

Front-loading fees can alleviate some of the financial pressure on the GPs, especially if the fund has not yet reached its fundraising target. It allows more resources to be allocated early on to build a stronger infrastructure for the fund, hire more personnel for operational support, and enhance the fund’s ability to scale and manage a larger portfolio.

However, there is of course a trade-off. If GPs fail to meet their fundraising goals or to raise a subsequent fund in time, they may face reduced budgets and will be forced to downsize their team, potentially impacting the fund’s performance.

LPs generally do not object to front-loaded fees, but GPs should exercise caution to avoid appearing too aggressive. Investors value alignment of interest. This is why, for example, charging 4% p.a. in the first 3 years and 8% during the next 7 years might send the wrong message.

The industry-standard management fee is 2% per year, often referenced in the popular “2 and 20” model. While it is not uncommon for funds to charge up to 2.5% p.a. (or 25% over the fund duration), anything above 2% is considered expensive and may be difficult to justify to investors during fundraising. Management fees exceeding 2.5% p.a. are generally deemed unreasonable and nearly impossible sell to investors.

Although LPs are willing to pay the market standard, funds with management fees below 2% p.a. are far more attractive to them for several reasons. Lower fees improve a fund’s economics by increasing its investable capital, allowing GPs to achieve the same net returns with a lower gross multiple, as illustrated in the chart below.

For example, a fund with a management fee of 1.5% p.a. (or 15% in total), would only require a 4.0x gross multiple to return 3.0x net to investors, while funds with 20% or 25% fees would require gross multiples of 4.25x and a 4.53x, respectively.

Additionally, lower fees will also increase alignment of interest between the fund and its LPs, as GPs will not be able to pay themselves high salaries and instead are financially incentivized to create carry.

Equalisation Interest

Equalisation interest, sometimes also referred to as “late payment interest”, is a payment made by investors who join a fund after its initial closing to earlier investors to compensate them for the time their capital was invested and at risk. This equalisation ensures that all investors, regardless of when they joined, have an equal financial footing, and it also creates a financial incentive for investors to make their commitment to the fund as early as possible.

New investors, essentially pay earlier investors interest on an “advance” on their share of previous capital contributions, covering the period from when those contributions were due up until their first drawdown from the fund. The equalisation interest is then distributed pro rata to earlier investors via the fund, either directly or by offsetting future capital calls. Importantly, the fund itself is not entitled to keep these equalisation payments.

The following formula can be used to calculate the equalisation interest amount for each previous drawdown of the fund. However, calculations can be increasingly complicated with more drawdowns, a large number of investors, or in the case of commitment increases:

Typically, the equalisation interest rate ranges from 4% to 10% p.a. depending on the fund. Some funds may even use a reference rate such as EURIBOR to determine their equalisation interest rate.

LPs, particularly larger institutional investors, are generally indifferent to equalisation interest since investors who commit to a large number of VC funds will often find that the amount of equalisation interest they pay is roughly equal to the amount they receive.

As a result, the impact of equalisation interest on their portfolio is quite marginal compared to the benefit of delaying a commitment to gain more visibility on a fund’s portfolio or its fundraising progress. Consequently, many VC funds choose not to charge equalisation fees to their investors, or only do implement them if they are asked to.

For smaller and less experienced LPs, however, equalisation fees can still be valuable, even if the impact on returns is modest. They serve as a strong incentive for them to invest to the fund as early as possible, which is very crucial for GPs to gain traction in their fundraising efforts.

Fund Expenses & Setup Costs

In addition to management fees, VC funds incur various operational expenses, that are not covered by the management fees. These fund expenses include costs related to making investments, such as legal fees, as well as ongoing operational costs like banking, depository, and annual audit fees. Typically, these fund expenses are borne by LPs, in accordance with the terms outlined in the fund’s LPA.

Additionally, the fund is responsible for covering the setup costs associated with establishing its legal structure. These setup costs are often initially paid by the GPs and later reimbursed after the fund’s initial closing.

Although the expenses are relatively modest - ranging from 0.1% to 0.5% of the committed capital annually for fund expenses and around 1% for the fund setup - they should not be overlooked. Many GPs neglect to fully account for these expenses in their fund models and budgets, which can lead to financial strain down the line.

Hurdle Rate & Catch-Up

In a VC fund, distributions to LPs occur in a specific sequence, known as distribution waterfall. Initially, all distributions are made to investors until the committed capital has been returned. In the next phase, distributions continue to be made solely to the investors until the fund’s hurdle rate is satisfied.

A hurdle rate, often also referred to as preferred return, represents the minimum rate of return that a fund must achieve on its investments before its general partners are entitled to receive their share of the fund’s profits, known as carry. This hurdle rate is most commonly structured as either an IRR based rate that is cumulative and compounds annually or a multiple based hurdle. Typically, funds aim for a rate of 6% to 10% p.a. or a multiple of 1.20x to 1.25x.

Once the hurdle rate is met, all subsequent distributions are made to the GPs as part of the GP catch-up phase. This catch-up mechanism allows the GPs to “catch up” on the share of profits that they would have received if the hurdle rate had not been in place. Once the catch-up phase is completed, all profits are split according to the agreed upon carry split, typically 20/80.

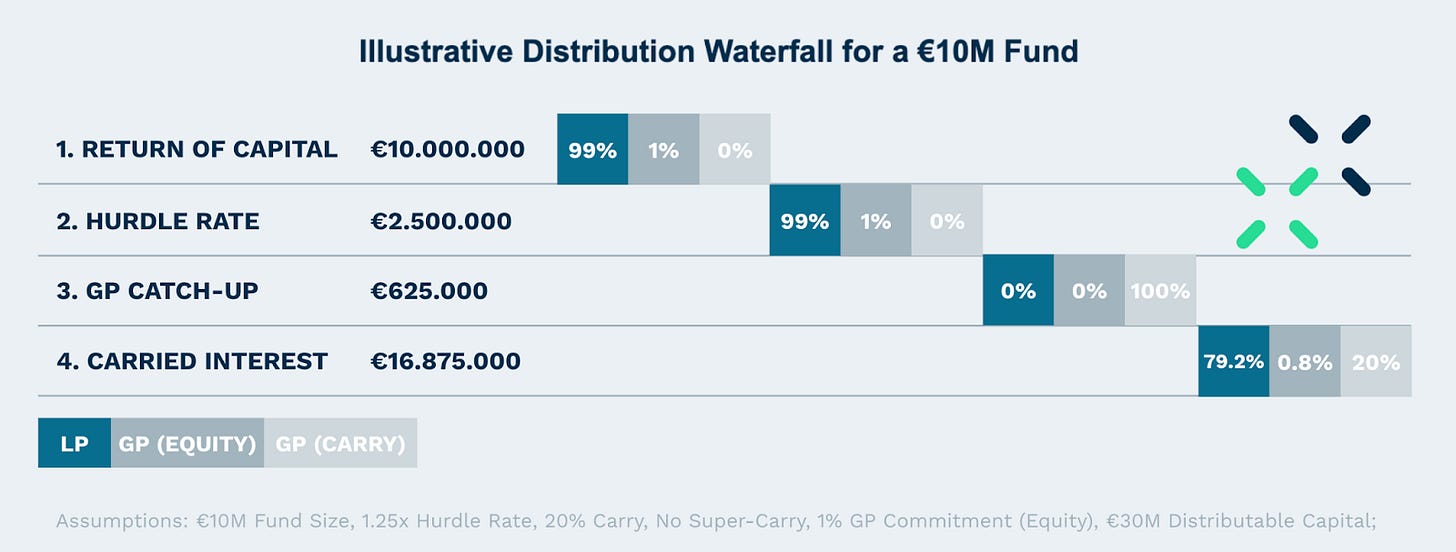

For example, consider a €10M fund with a 1.25x hurdle rate and 20% carry that is able to distribute €30M to investors. Initially, the fund will return the committed capital of €10M to investors (LPs and the GPs’ equity stake). Next, investors receive €2.5M as the preferred return. After this, the GPs receive their first carry of €625k as part of the GP catch-up, ensuring that all profits of €3.125M have been split 20/80. Finally, the remainder of €16.875M is distributed equally according to the same 20/80 ratio.

The majority of LPs don’t place any significant importance on hurdles rates, as they are unlikely to have a substantial impact on their overall returns. In fact, hurdle rates primarily come into play when a fund is already underperforming. In the example above, the hurdle rate would only benefit LPs if the gross DPI is between 1.00x and 1.31x (during the hurdle rate & catch-up phase).

Whether or not the GPs of the fund receive carry on such low multiples, will not significantly affect an LP’s overall returns, especially within a well diversified VC portfolio. With a hurdle rate, LPs could at most improve their returns by 5% if the DPI is exactly at 1.25x. As a result, many VCs are nowadays deciding against a hurdle rate, which eliminates the need for catch-up mechanism and simplifies their distribution waterfalls.

Carried Interest (European & American Waterfalls)

Carried Interest, also referred to as “carry” or “performance fee”, is the share of profits earned by GPs. The market standard for carry in VC funds is 20%, although some funds may decide to charge fees as high as 25% or 30%, making them of course less desirable to prospective investors.

While carried interest is mostly discussed as a percentage of profits, the actual amount of carry earned by GPs largely depends on the fund’s distribution waterfall. Carry payouts generally follow one of two models: the European waterfall or the American waterfall, also known as “deal-by-deal carry”.

In the European waterfall, as outlined in the previous section, the fund must first return 100% of the committed capital to investors and meet the agreed-upon hurdle rate, before carry can be paid out during the catch-up phase and eventually distributions are split 20/80 between GPs & LPs.

The American waterfall, on the other hand, applies the same payout structure to each individual investment made by the fund. This means that for every successful investment, GPs can receive their carry once the capital used for that particular investment is repaid, without needing the entire fund to be profitable.

For example, consider a €10M fund that makes 10 investments of €1M each, with only one investment returning €10M in distributions. Under the European waterfall, all €10M would be returned to the LPs, and the GPs would not receive any carry. Under the American waterfall, however, GPs would only need to return the investment costs of €1M to investors, before being able to receive €1.8M in carry, even though the fund as a whole only broke even.

While this is an extreme example, it highlights how LPs can be negatively impacted by an American waterfall, potentially paying carry on funds that fail to return their committed capital or paying higher carry fees on profitable funds with a single outlier company. Since this model originated in the private equity industry, where investments are fewer and failure rates are lower, it is less suited to a power law driven industry where the opposite is the case and most VCs don’t manage to return their funds.

Although the European waterfall is the industry standard, some VC funds still use an American waterfall. Experienced LPs will carefully review the legal documentation of any fund they are considering and try to avoid funds with an American waterfall distribution at all costs. This is especially necessary because many GPs, especially among emerging managers, may not even be aware of or understand the type of distribution waterfall their fund employs.

Super Carry

Super Carry, sometimes also known as “tiered carry”, refers to an enhanced or increased percentage of the carried interest that GPs receive. This higher carry is triggered when the fund’s returns exceed a predetermined threshold. Once this threshold is met, GPs receive a greater share of the profits than they would under the standard carried interest rate, typically 25% or 30% instead of the standard 20%. Of course, for this threshold, the fund may also have a catch-up period where all excess returns are allocated to the GPs until all cumulative profits have been split by the new super carry rate.

LPs generally view super carry unfavourably because it undermines the attractiveness of venture capital as an asset class. Like VCs, LPs' portfolios are subject to the power law, where a few highly successful funds generate the majority of returns. If these top-performing funds increase their carry, the overall returns for LPs would be significantly lower. As a result, the risk-return profile of VC becomes less appealing, making the asset class less attractive to LPs.

Although super-carry has gained popularity recently, especially among emerging managers, it is generally not recommended for funds, particularly for first-time funds. For those without a proven track record of high returns, introducing a super-carry can make fundraising significantly more challenging as LPs may be hesitant to invest if the managers have not yet demonstrated their ability to achieve the necessary returns.

That said, if a fund can show a reasonable fee structure and evidence that it can deliver strong returns, some LPs may be willing to accept a super-carry. Although, this is only true for a very small number of funds.

VCs who are in favour of having a super carry should be aware that most LPs would not invest in funds with a catch-up on their super carry and generally only accept super carry after a threshold of at least 3.0x net distributions to investors. Moreover, super-carry in combination with a high management fee of more than 20% is also frowned upon by LPs.

Thank you for taking the time to read our blogpost! For more information about Multiple Capital, please visit our website or reach out to our team directly.

In venture capital, the right fee structure can make or break investor confidence—transparency is key.

Excellent insights on super carry which is strongly encouraged in many emerging manager accelerator programs. Appreciated!